Industrial - Commercial

Industrial - Commercial  Electrical

Contractor

Electrical

Contractor

PDQ Electric Corp

NJ, PA, DE, MD, NY, CT, DC, MA, RI

|

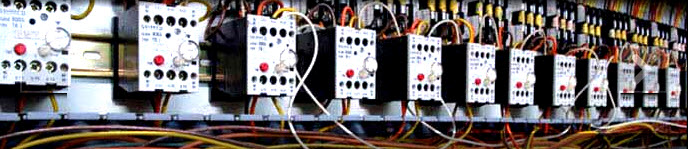

PDQIE - PDQ Industrial ElectricElectroplating (Electro-Deposition)Electroplating

Electroplating is a plating process in which metal ions in a solution are moved by an electric

field to coat an electrode. The process uses electrical current to reduce cations of a desired material

from a solution and coat a conductive object with a thin layer of the material, such as a metal. Electroplating

is primarily used for depositing a layer of material to bestow a desired property (e.g., abrasion and wear

resistance, corrosion protection, lubricity, aesthetic qualities, etc.) to a surface that otherwise lacks

that property. Another application uses electroplating to build up thickness on undersized parts.

The process used in electroplating is called electro-deposition. It is analogous to a galvanic cell acting in reverse. The part to be plated is the cathode of the circuit. In one technique, the anode is made of the metal to be plated on the part. Both components are immersed in a solution called an electrolyte containing one or more dissolved metal salts as well as other ions that permit the flow of electricity. A power supply supplies a direct current to the anode, oxidizing the metal atoms that comprise it and allowing them to dissolve in the solution. At the cathode, the dissolved metal ions in the electrolyte solution are reduced at the interface between the solution and the cathode, such that they "plate out" onto the cathode. The rate at which the anode is dissolved is equal to the rate at which the cathode is plated, vis-a-vis the current flowing through the circuit. In this manner, the ions in the electrolyte bath are continuously replenished by the anode. Other electroplating processes may use a nonconsumable anode such as lead. In these techniques, ions of the metal to be plated must be periodically replenished in the bath as they are drawn out of the solution.[2 ]

PROCESS

The anode and cathode in the electroplating cell are both connected to an external supply of direct current - a battery or, more commonly, a rectifier. The anode is connected to the positive terminal of the supply, and the cathode (article to be plated) is connected to the negative terminal. When the external power supply is switched on, the metal at the anode is oxidized from the zero valence state to form cations with a positive charge. These cations associate with the anions in the solution. The cations are reduced at the cathode to deposit in the metallic, zero valence state. For example, in an acid solution, copper is oxidized at the anode to Cu2+ by losing two electrons. The Cu2+ associates with the anion SO42- in the solution to form copper sulfate. At the cathode, the Cu2+ is reduced to metallic copper by gaining two electrons. The result is the effective transfer of copper from the anode source to a plate covering the cathode. The plating is most commonly a single metallic element, not an alloy. However, some alloys can be electrodeposited, notably brass and solder. Many plating baths include cyanides of other metals (e.g., potassium cyanide) in addition to cyanides of the metal to be deposited. These free cyanides facilitate anode corrosion, help to maintain a constant metal ion level and contribute to conductivity. Additionally, non-metal chemicals such as carbonates and phosphates may be added to increase conductivity. When plating is not desired on certain areas of the substrate, stop-offs are applied to prevent the bath from coming in contact with the substrate. Typical stop-offs include tape, foil, lacquers, and waxes. StrikeInitially, a special plating deposit called a "strike" or "flash" may be used to form a very thin (typically less than 0.1 micrometer thick) plating with high quality and good adherence to the substrate. This serves as a foundation for subsequent plating processes. A strike uses a high current density and a bath with a low ion concentration. The process is slow, so more efficient plating processes are used once the desired strike thickness is obtained. The striking method is also used in combination with the plating of different metals. If it is desirable to plate one type of deposit onto a metal to improve corrosion resistance but this metal has inherently poor adhesion to the substrate, a strike can be first deposited that is compatible with both. One example of this situation is the poor adhesion of electrolytic nickel on zinc alloys, in which case a copper strike is used, which has good adherence to both. Current DensityThe current density (current of the electroplating current divided by the surface area of the part) in this process strongly influences the deposition rate, plating adherence, and plating quality. This density can vary over the surface of a part, as outside surfaces will tend to have a higher current density than inside surfaces (e.g., holes, bores, etc.). The higher the current density, the faster the deposition rate will be, although there is a practical limit enforced by poor adhesion and plating quality when the deposition rate is too high. While most plating cells use a continuous direct current, some employ a cycle of 8–15 seconds on followed by 1–3 seconds off. This technique is commonly referred to as "pulse plating" and allows high current densities to be used while still producing a quality deposit. In order to deal with the uneven plating rates that result from high current densities, the current is even sometimes reversed in a method known as "pulse-reverse plating", causing some of the plating from the thicker sections to re-enter the solution. In effect, this allows the "valleys" to be filled without over-plating the "peaks". This is common on rough parts or when a bright finish is required. In a typical pulse reverse operation, the reverse current density is three times greater than the forward current density and the reverse pulse width is less than one-quarter the forward pulse width. Pulse-reverse processes can be operated at a wide range of frequencies from several hundred hertz up to the order of megahertz. Brush electroplatingA closely-related process is brush electroplating, in which localized areas or entire items are plated using a brush saturated with plating solution. The brush, typically a stainless steel body wrapped with a cloth material that both holds the plating solution and prevents direct contact with the item being plated, is connected to the positive side of a low voltage direct-current power source, and the item to be plated connected to the negative. The operator dips the brush in plating solution then applies it to the item, moving the brush continually to get an even distribution of the plating material. The brush acts as the anode, but typically does not contribute any plating material, although sometimes the brush is made from or contains the plating material in order to extend the life of the plating solution. Brush electroplating has several advantages over tank plating, including portability, ability to plate items that for some reason cannot be tank plated (one application was the plating of portions of very large decorative support columns in a building restoration), low or no masking requirements, and comparatively low plating solution volume requirements. Disadvantages compared to tank plating can include greater operator involvement (tank plating can frequently be done with minimal attention), and inability to achieve as great a plate thickness. Electroless depositionUsually an electrolytic cell (consisting of two electrodes, electrolyte, and external source of current) is used for electrodeposition. In contrast, an electroless deposition process uses only one electrode and no external source of electric current. However, the solution for the electroless process needs to contain a reducing agent. In principle any water-based reducer can be used although the redox potential of the reducer half-cell must be high enough to overcome the energy barriers inherent in liquid chemistry. Electroless nickel plating uses hypophosphite as the reducer while plating of other metals like silver, gold and copper typically use low molecular weight aldehydes. A major benefit of this approach over electroplating is that power sources and plating baths are not needed, reducing the cost of production. The technique can also plate diverse shapes and types of surface. The downside is that the plating process is usually slower and cannot create such thick plates of metal. As a consequence of these characteristics, electroless deposition is quite common in the decorative arts. CleanlinessCleanliness is essential to successful electroplating, since molecular layers of oil can prevent adhesion of the coating. ASTM B322 is a standard guide for cleaning metals prior to electroplating. Cleaning processes include solvent cleaning, hot alkaline detergent cleaning, electrocleaning, and acid etc. The most common industrial test for cleanliness is the waterbreak test, in which the surface is thoroughly rinsed and held vertical. Hydrophobic contaminants such as oils cause the water to bead and break up, allowing the water to drain rapidly. Perfectly clean metal surfaces are hydrophilic and will retain an unbroken sheet of water that does not bead up or drain off. ASTM F22 describes a version of this test. This test does not detect hydrophilic contaminants, but the electroplating process can displace these easily since the solutions are water-based. Surfactants such as soap reduce the sensitivity of the test and must be thoroughly rinsed off. EffectsElectroplating changes the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of the workpiece. An example of a chemical change is when nickel plating improves corrosion resistance. An example of a physical change is a change in the outward appearance. An example of a mechanical change is a change in tensile strength or surface hardness. Call PDQIE to Set-Up Your Electroplating Facility (877) PDQ-4-FIX | |

(877) 737-4349 (Toll Free)

(877) PDQ-4-FIX (Toll

Free)

(856) 625-6969 (Text

Messaging)

PDQ ia an Acronym for "Pretty Damn Quick"

|

PDQIE, www.PDQIE.com, info@PDQIE.com, quote@PDQIE.com, Ryan@PDQIE.com, PDQ Industrial Electric, www.PDQIndustrialElectric.com, info@PDQIndustrialElectric.com, quote@PDQIndustrialElectric.com, Ryan@PDQIndustrialElectric.com are marketing tools of PDQ Electric Corp, a NJ Licensed Electrical Contractor. Reddy Kilowatt® is a Registered Trademark of Northern States Power Company. The information on this website is believed to be reliable, but we cannot guarantee that information will be accurate, complete and current at all times and should be reaffirmed by a licensed professional before relying on it. PDQIE will from time to time revise information, products and services described in-on this Website, and reserves the right to make such changes without notice. Use of this Website is entirely at your risk. Materials and information in this Website (including text, graphics, and functionality) are presented without express or implied warranties of any kind and are provided "as is". It is your responsibility to evaluate the accuracy, completeness and usefulness of any opinions, advice, services and information provided.